In Magdalena, turn south on the road adjacent to the ranger station. Take the left fork l.9 miles later at the smelter foundation. The church and cemetery at Kelly are 1.4 miles from that fork. South of Magdalena and west of Kelly is Magdalena Peak, so named, according to one legend, because a group of Mexicans were about to be slaughtered by Apaches when the face of Mary Magdalene appeared on the mountain, terrifying the Apaches and saving their intended victims.

Another story says that the peak was named because a face said to be Mary Magdalene’s is discernible on the north end of the mountain. For whatever reason, the peak had some sort of significance to the Apaches, for as the miners picked their way over the canyons, gulches, and cliffs of the Magdalena Mountains, the Apaches never once attacked those miners working the slopes near the peak.

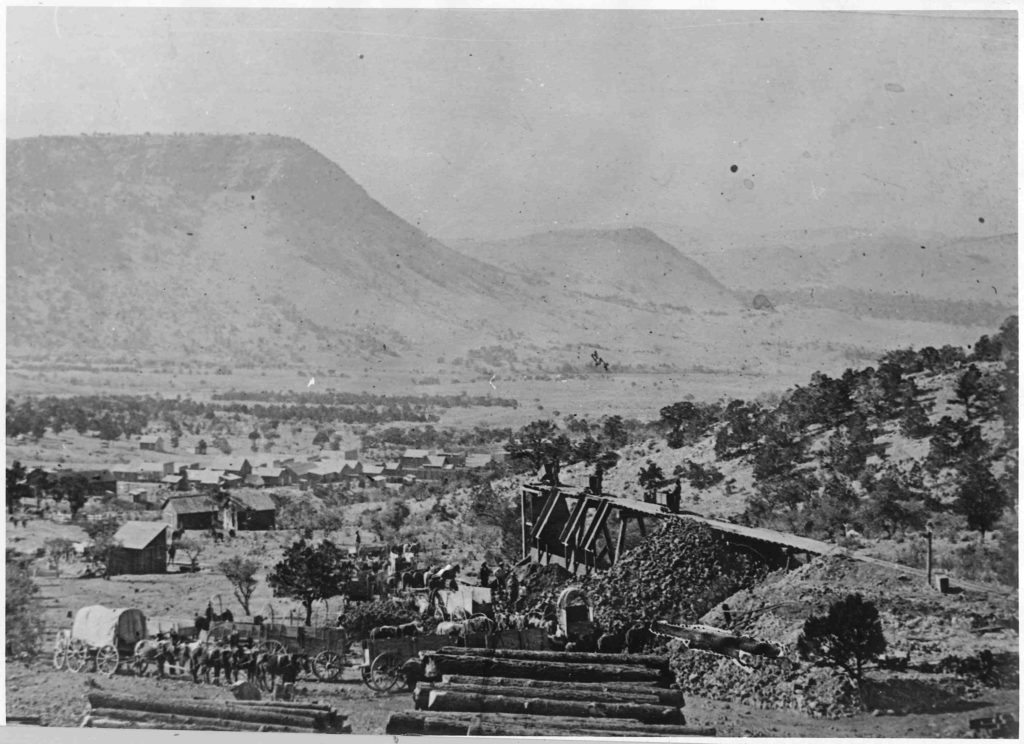

Colonel J. S. Hutchason was the one who started the mad scramble in the Magdalena’s. In 1866 he filed two claims after finding outcroppings rich in lead. He gave a third claim to Andy Kelly, a friend who worked a sawmill. Hutchason kept an eye on the claim, however, and when Kelly failed to do the proper assessment work, Hutchason jumped it. By 1870 the town came to life as miners discovered lead, zinc, silver, copper, and even some gold.

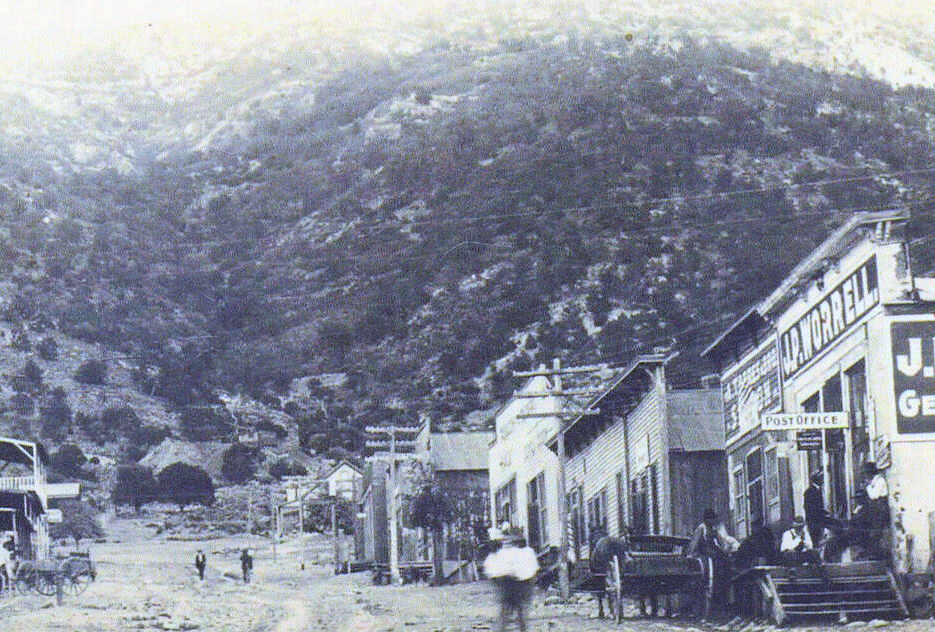

The town was named Kelly, perhaps in mirth at the man who had lost his claim, perhaps because of guilt pangs. When the railroad arrived at Magdalena in 1880, operations at Kelly became more profitable since ore no longer had to be freighted by m team to Kansas City. The railroad wanted to build a spur a the way to Kelly, but the rapid ascent made the line impractical, so the ore was hauled down to Magdalena using sixteen mule and horse teams.

The post office came to Kelly in 1883. Eventually the town featured two hotels, two churches, two dance halls, seven saloons, and an estimated population of three thousand. Just after the turn of the century, as silver deposits began to play out and zinc and lead became the major minerals of the area, Cory T Brown of Socorro had a greenish rock assayed that had long been discarded in the

waste dumps of Kelly. It turned out to be zinc carbonate, also known as smithsonite, a substance used as pigment in paints. Kelly had new life. The Sherwin Williams Paint Company bought the Graphic Mine from Brown and his partner, J. B. Pitch.

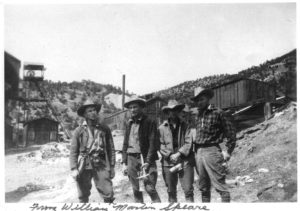

The Tri-Bullion Company bought the Kelly Mine, and the town expanded with new wealth. But by 1931 the smithsonite had been extricated, and Kelly began to die. At this time, over thirty million dollars in mineral wealth had been taken From the Magdalena Mountains.

The post office hung on until 1945. Smelter foundations, a small white stucco Catholic church, a juniper and pinon-filled cemetery, a few walls and foundations, and an old vault are all that remain of the town of Kelly. A bit farther up the canyon are the remains of the Tri-Bullion Mine, earlier known as the Kelly.