Opened in 1885, the New Mexico Penitentiary had been authorized by Congress since 1853. The design was based on the same plans used for Sing Sing and Joliet.

Beginning in 1903, New Mexico became the first western state to employ prisoners in building highways. The early prison industry in New Mexico produced bricks.

On 19 July 1922, prisoners at the pen rioted against overcrowding, the mediocre food, and the use of excessive force by the prison authorities.[8] When the inmates refused to return to their cells, the tower guards opened fire, killing one inmate and injuring five others. In the report following the riot, the prison authorities were blamed for lack of experience, and failure to understand how to control a prison population.

The second riot was 15 June 1953. Inmates protesting the use of excessive force seized Deputy Warden Ralph Tahash and twelve guards and held them hostage. In the resulting melee, guards killed two inmates and wounded many others. This second riot led to the abandonment of the original facility as a prison and the construction in 1956 of what came to be called “the main unit.”

The third riot occurred in 1980 and became the most infamous. It is often described as the scene of one of the most violent prison riots in the correctional history of America. In a two day period, over two days 33 inmates were killed and 12 officers were held hostage by prisoners who had escaped from cell blocks in the main unit. Men were brutally butchered, dismembered, and decapitated and hung up on the cells and burned alive. This section of the prison was closed in 1998 and is now referred to as “Old Main.”

The 1980 riot was an inmate rebellion that did not have a plan, leadership, and lacked any defined goals. There were few heroes, plenty of villains and many victims. When State Police marched into the Penitentiary of New Mexico on Feb. 3, 1980, they didn’t retake the prison from rioting inmates so much as they occupied the charred shell after the riot had burned itself out. Thirty-three inmates were found dead inside — some of them horribly butchered by their fellow prisoners.

The emergency room at St. Vincent Hospital in Santa Fe was overwhelmed with more than 100 inmates. Some of them had been severely beaten while others were suffering from drug overdoses. Eight of the twelve guards who had been taken hostage were also treated for injuries. It was amazing that not a single guards had been killed. The riot became a black mark on New Mexico’s history as the national press was captivated by the horror stories that leaked out of Santa Fe.

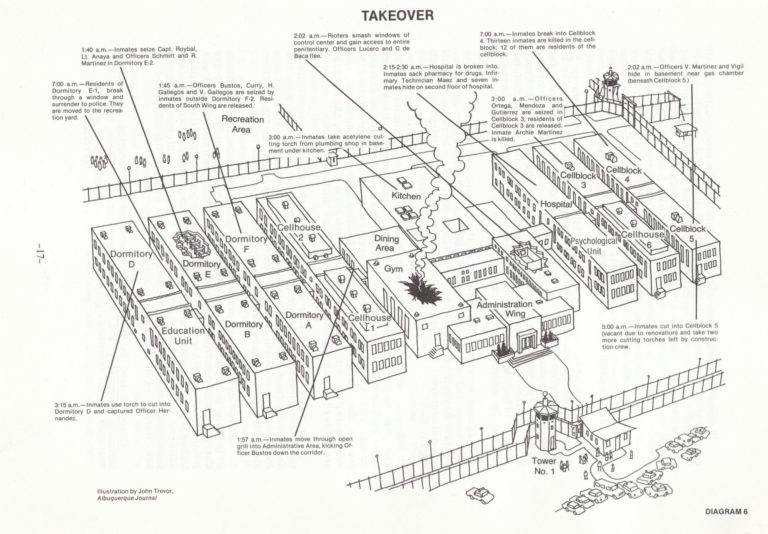

The riot started in the early morning of Saturday, Feb. 2, when guards entered dormitory E-2 on the south side of the Prison to do their nightly head counts. Making matters worse, the

dormitory now contained several maximum security inmates that had been transferred there due to renovations in their cell block. In violation of prison security procedures. The door to the dormitory wasn’t locked after the guards entered the room to complete their rounds. The inmates charged the guards and subdued them quickly. Within the first few minutes of the riot four guards were taken, hostage. Using the keys that had been taken from the officers, inmates freed fellow prisoners then moved through an open grill gate, which was also unlocked, to the administrative area. Once there they smashed their way into the main control center and gained access to every part of the main penitentiary building where 1,157 male inmates were under the custody and care of 25 correctional employees. The guard on duty fled, leaving behind keys that could open most of the prison gates and doors. The inside of the prison quickly became a nightmare of devastation and violence. One Associated Press reporter later described it in a story distributed worldwide as a “merry-go-round gone crazy.”

Fires were set around various locations around the prison. The inmates had also ripped out plumbing fixtures, flooding parts of the building. Other inmates got into the infirmary and began taking drugs. As the riot escalated, so did the violence. Inmates who were gang members started hunting their enemies and found them. Then, sometime around 8 a.m. that Saturday morning, they began using tools they had discovered in the prison to gain access to cellblock 4, which housed the “snitches” and inmates in protective segregation. The majority of the “snitches” met a horrible end. One unfortunate inmate was hung from the upper tier of the cellblock, another had been decapitated. Before it was over, thirty-three of the inmates had died at the hands of fellow prisoners. Some of the victims were also tortured and their bodies mutilated. At least 90 other inmates were seriously injured in the riot, suffering from drug overdoses or beatings, stabbings, and rapes inflicted by other convicts. Most of the inmates had escaped to the outside of the walls by the time the riot was over

Early Saturday morning, fitful negotiations began with some inmate leaders. Ambulances shuttled the dead and injured to St. Vincent. Smoke poured out of the prison gymnasium.

It became clear later that neither the inmates nor the state had a single spokesman during the negotiations. Eventually, inmates made 11 basic demands. Some concerned necessary prison conditions like overcrowding, inmate discipline, educational services and improving food. They also wanted outside witnesses — federal officials and the news media.

Guards that were held as hostages were released. Some of the guards had been protected by inmates; others were brutally beaten. “One was tied to a chair. Another lay naked on a stretcher, blood pouring from a head wound,” a Journal reporter wrote. Negotiations broke off about 1 a.m. Sunday and state officials insisted no concessions had been made. But the riot, fueled by drugs and hate, was running out of gas.

Later Sunday morning, inmates began to trickle out of the prison, seeking refuge at the fence where National Guardsmen were armed with M-16s. Black inmates led the escape from the smoldering building, staying in groups large enough to defend themselves from other inmates. By 1:30 p.m. Sunday, Feb. 3, 1980, the violence had spent itself; police and National Guardsmen retook the prison without resistance.

After the riot, new facilities were constructed to the north and south of the main prison. New prison facilities were also built near Las Cruces, Los Lunas and Grants to ease the overcrowding issue. Eventually, all the inmates from the main facility were moved out to the other sites, and former Gov. Gary Johnson closed the main facility in 1998.

Sources:

“Report of the Attorney General on the February 2 and 3, 1980 Riot at the Penitentiary of New Mexico: Part I The Penitentiary, The Riot, The Aftermath,” Report Mandated By Section 9, Chapter 24, Laws of 1980. Attorney General: Jeff Bingaman

Walk the Straight Line | It was an inmate rebellion …. https://www.flickr.com/photos/rhdphotography/3017211585