The information presented here is from the Valencia County Newspaper in an article called La Historia del Rio Abajo The Kuhn Hotel: An Endangered Historic Property, Story by Richard Melzer, guest columnist and Jim Sloan.

Early maps of Belen show the property where the hotel stands was once used for very different purposes. About the turn of the 20th century, a building with Belen’s Commercial Club and Heyday Club, which included the town’s first bowling alley, once occupied the space beside the tracks. A small bakery stood just west of the Heyday Club, on North Second Street.

But the Heyday Club and its building were gone when a woman named Ruth Kuhn moved to Belen. Ruth had first come to New Mexico with her husband, Louis, and young son, Louis Jr. Traveling by covered wagon, the family entered the territory via Tucumcari and settled in Albuquerque’s South Valley by 1885.

According to family legend, Ruth ran the family farm while Louis worked as a blacksmith. All went well until Louis suddenly left, abandoning Ruth and her kids, Louis Jr. (born in 1882), Leo (born in 1887) and Stella (born in 1894). The couple apparently reconciled and moved to Baxter, Texas, with Ruth running a boarding house for a short while. But all did not go well, and the Kuhns separated once more. Returning to New Mexico, Ruth settled in Belen, where she worked at and eventually owned a bakery and restaurant. Unfortunately, the only thing we know about Ruth’s enterprise is that the Belen News reported that someone had broken into her bakery and stolen some cakes, pies and an entire cash register late one Saturday night in 1911.

Despite this setback, Ruth apparently managed to save enough money to invest in a hotel. She might well have received financial assistance from the First National Bank of Belen. Women securing business loans was almost unheard of in those days, but there was a fortunate precedent in Belen.

Owned and operated by John Becker, the First National Bank had helped finance the building of the Belen Hotel, which opened in 1907. Always an astute businessman, Becker knew that hotels were needed with the completion of the Belen Cut-Off by the Santa Fe Railway. Bertha Rutz, a German nanny who had cared for the Becker children, ran the Belen Hotel for nearly 50 years. Becker may well have financed the Kuhn Hotel because he recognized Ruth’s business skills and realized that Belen needed more than one hotel to keep up with the new railroad demands.

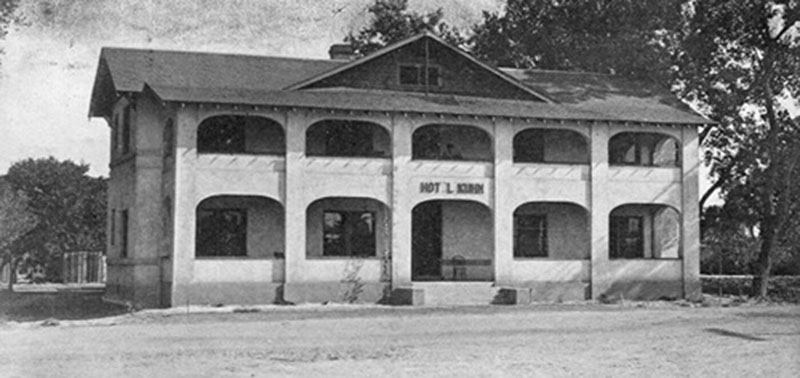

By 1913, the Belen city directory listed Ruth as a provider of room and board. By World War I, her business was well-established in a two-story hotel built on 5-foot deep footings and with 3-foot wide adobe walls. Guests arrived at the Kuhn Hotel at all hours of the day and night. Once inside, they signed in at a registration desk next to the main entrance. Long before electricity and running water were installed, each new guest received two essential items — a kerosene lantern and a chamber pot. Chamber pots were to be left outside of guest rooms each morning so that house maids could collect them, empty them and wash them with vinegar. Maids cleaned the rooms and provided fresh linen, as needed.

Ruth Kuhn provided one meal a day for her guests. Other customers paid 25 cents for her daily blue-plate special. Ruth was also known to make large bowls of iced tea and lemonade for her guests as they sat on the hotel’s balcony, especially as they watched town parades pass by on First Street.

In a more trusting age, the hotel’s front doors were left unlocked to allow railroad workers and call boys to come and go as their schedules required. Call boys knocked on the workers’ guest-room doors to summon them to join railroad crews, as needed. Some guests were known to frequent notorious local bars until late at night. Ruth prohibited liquor in her hotel and did not tolerate guests she caught arriving after a night of drinking at places like the Railroad Club up the street. Many a guest was pushed out the door by Ruth armed with her favorite weapon, a broom.

In one famous incident, a guest returned to the hotel in an inebriated state. Getting past Ruth, the man began to climb the hotel’s stairs when an equally intoxicated, armed stranger ran into the hotel and shot the guest dead. Witnessing the fracas, Ruth ordered that the dead man’s body be dragged down the street and dumped in front of the Railroad Club. It seemed only fair that the place that had caused the problem be responsible for its results.

While Ruth banned alcohol on her premises, she reserved the right to indulge, at least when she was out of town. As the owner of a large, shiny Oldsmobile, Ruth hired a driver who drove her to and from her favorite place of amusement in Jarales.

The hotel had various owners in the 1930s during the Great Depression. By 1940, it was sold to Bernard J. Vanderwagen, who completely refurbished the building, now referred to in the press as a “landmark in Belen.” Vanderwagen then leased the hotel to Garland M. Whittington, who also ran a boarding house on West Gold Avenue in Albuquerque. Signing a five-year lease, the Whittingtons moved to Belen and joined the local Chamber of Commerce. Unfortunately, 62-year-old Garland died at the hotel in October 1943.

The Great Depression of the 1930s was unkind to nearly every business, including hotels in Belen. Few Americans could afford to take vacations and the railroad often laid off employees or reduced their work hours. To make matters worse, those who traveled increasingly used cars, buses and planes rather than trains. Hotels near train depots suffered, often to be replaced by motels along new highways.

Making a profit in the hotel business was a challenge before, during and after the Depression. Owners of the Kuhn Hotel looked for alternative ways to make money, with mixed results. At some point, the hotel’s baths must have been rented out as public baths. Signs found in the basement advertised baths for 10 cents and shaves for 25 cents.

In March 1927, Dr. Gaines ran newspaper ads to announce that he would be at the Kuhn Hotel for six hours to consult with women about surgeries that did not require the use of knives. Hearing of this transient doctor and his suspicious procedure, many Belenites probably suspected a quack. Local women also went to the hotel for beauty services in 1930. According to an ad in the Belen newspaper, ladies could call the hotel to make appointments for haircuts and settings offered at the hotel every Tuesday. Employees of the Albuquerque-Chicago College of Beauty Culture gave permanent waves for $5, equal to $75 in today’s money.

The Kuhn Hotel served as temporary headquarters for a rather suspicious sounding operation in early 1955. An ad in the Albuquerque Journal told readers that a Mr. McCoy would be available at the hotel to meet with “four neat appearing men or women living in Belen.” Mr. McCoy guaranteed that the fortunate four would be eligible for a “fast money-making proposition.” No experience was necessary, and no other details were provided.

A more legitimate businessman set up shop in the hotel in the 1950s and 1960s. A commercial photographer offered his skills for portraits taken on the hotel’s second floor. Many children receiving their First Holy Communions had their angelic photos taken at the Kuhn Hotel. The photographer also took pictures of graduations, proms and other special occasions. Another talented person offered artistic services at the hotel. Despite the need for quiet with so many railroad workers trying to sleep day and night, a piano teacher gave lessons to local children. We do not know where the lessons were taught with the least impact on light sleepers.

The hotel had fallen on hard times by the early 1960s. A classified ad in the Albuquerque Journal was slightly more descriptive than the “for sale” ad that had run in 1929, but its wording was not optimistic: “Kuhn Hotel for sale as is. 24 units. Make offer. 100 Reinken Ave., Belen.”

The hotel’s owner, Albert Villenueve, had no reason to be optimistic in March 1962 when his ad appeared. He had recently filed a lawsuit against the state for damages it had caused by building a new overpass directly in front of his property. Other businessmen also protested, knowing the overpass would divert traffic and many potential customers. The use of sledgehammers and other powerful construction equipment would cause major damage to older structures like the hotel.

But the protests were to no avail. Businesses and residents on the east side of the Santa Fe Railway’s tracks had long complained about lengthy delays as long trains pulled in and out of Belen’s busy train yards.

Blais made several changes at the hotel he purchased in 1964, starting with its name. Realizing that the Kuhn name had racist connotations, Blais changed the name to the City Hotel at the height of the civil rights movement of the 1960s. He never discriminated against guests, vowing that anyone could stay at the hotel as long as they could pay their bill.

Blais sold the hotel to Roland Kindsvater in 1972. Blais died of cancer in October of that year. Alan “Dean” Noftsker eventually purchased the hotel, running it as a boarding house and exploring other money-making opportunities. Dean ran a Thieves’ Market in the hotel lobby, selling antiques, jewelry and other items. Dean made much of the jewelry he sold, using a back room of the hotel for production. He reportedly hired Mexican workers from across the border to help in his jewelry-making enterprise. When border agents occasionally arrived at the hotel, the illegal workers would jump through a trap door in the floor to hide. A rug was thrown over the trap door to conceal its lower chamber. Everyone resurfaced and got back to work as soon as the coast was clear.

Lloyd Sais bought the business when Dean passed away. Hoping to restore the hotel, Lloyd did a lot of work, cleaning up and working on the electricity. He remembers the uphill battle he faced, especially with the old sewer line and aging roof.

Joan Artiaga purchased the property in 2003. As its 13th owner, Joan planned to restore the building and convert it into an art center with studios, galleries and places for artists to teach, work and live. She and her husband, Pasqual Armijo, made good progress, but faced three main obstacles.

First, as with any old building, the hotel’s roof needed major, very expensive repairs. No matter how much was done to the interior, leaks caused continual damage to the inside. Dealing with the roof and the damage it caused was like taking three steps forward and two steps back.

The next main problem that Joan faced was the Reinken Avenue overpass. The original overpass had been the beginning of the end of the hotel. Two new overpasses built since 1962 have caused additional structural damage and have further reduced access to the property. Complaints to the city have fallen on deaf ears. Adding insult to injury, Joan has faced thousands of dollars worth of damage caused by vandalism. In her first two years as owner, Joan experienced more than a hundred break-ins, with vandals breaking windows, painting graffiti, leaving beer cans and stealing tools, equipment and pieces of art. The police patrol the area and have been called to the site countless times, but the hotel’s isolation and the lack of city lighting has made the property more vulnerable than ever. Not even the presence of a caretaker has made a difference.