The story of Quanah Parker and the Comanche nation is a tale of resilience, transformation, and ultimately, the loss of one of the most powerful Native American empires on the North American plains. As the last chief of the Comanches, Quanah Parker symbolizes the intersection of two worlds: the traditional life of the Native tribes and the encroaching dominance of Western settlers and their governments. This article will explore the rise of the Comanche empire, their dominance over the Great Plains, the eventual decline of their power, and Quanah Parker’s unique role in this transformative period.

The Comanches, originally part of the Shoshone people, began their migration southward into the Great Plains around the early 18th century. Their move was facilitated by one critical factor: the horse. After the Spanish introduced horses to North America in the late 16th century, the Comanches quickly adapted to a mounted lifestyle, revolutionizing their culture, economy, and military strategies. This transformation made them one of the most formidable powers in the region.

The Comanche empire, known as Comancheria, spanned parts of modern-day Texas, Oklahoma, New Mexico, and Kansas. By the mid-18th century, the Comanches had established themselves as dominant players in the region, controlling trade routes, engaging in diplomacy with neighboring tribes, and fiercely resisting European encroachment. They were masterful horsemen and warriors, using their mobility to conduct raids and defend their territories. This earned them a fearsome reputation among settlers and rival tribes alike.

The Comanche dominance over the Great Plains reached its apex in the early 19th century. They were known as the “Lords of the Plains,” a testament to their unparalleled mastery of the horse and their ability to thrive in the harsh, arid environment of the region. Their economy revolved around hunting, raiding, and trading. Buffalo provided the Comanches with food, clothing, and shelter, while horses became a form of wealth and status.

The Comanches engaged in an extensive trade network, exchanging goods like buffalo hides, horses, and captives with other tribes, as well as with European settlers. They also conducted raids on Mexican settlements and other tribes, taking captives who were either ransomed or assimilated into the Comanche way of life.

During this period, the Comanches were not only warriors but also skilled diplomats. They entered into strategic alliances and negotiated treaties to maintain their dominance. However, their golden age was not without challenges. Intertribal conflicts, competition with other Native groups, and the arrival of increasing numbers of European settlers began to strain their resources.

The decline of the Comanche empire was a gradual process, influenced by a combination of external pressures and internal challenges. By the mid-19th century, several factors began to erode their power.

- Disease and Population Decline: European diseases like smallpox and cholera devastated the Comanche population, as they did for countless other Native American tribes. Lacking immunity to these illnesses, the Comanches suffered significant population losses, weakening their ability to defend their territory.

- The Buffalo Extermination: The Comanche way of life was inextricably tied to the buffalo. However, by the 1870s, the mass slaughter of buffalo by white hunters, often encouraged by the U.S. government as a way to starve Native populations, decimated the herds. This struck at the very heart of Comanche culture and survival.

- Military Defeat: The Comanches faced increasing military pressure from the U.S. Army, which sought to clear the plains for settlers. The Red River War of 1874-1875 was a turning point. After a series of battles and the destruction of their winter supplies, the Comanches were forced to surrender. Their defeat marked the end of their dominance over the Great Plains.

- Encroachment and Treaties: The westward expansion of settlers, driven by policies like the Homestead Act of 1862, brought an influx of people into Comanche territory. Treaties, often signed under duress or broken by the U.S. government, further reduced their land and autonomy.

In the midst of this decline, a young leader emerged who would become the last chief of the Comanches: Quanah Parker. His life story is emblematic of the cultural crossroads at which the Comanches found themselves in the late 19th century.

Quanah Parker was born around 1845 to a Comanche chief, Peta Nocona, and Cynthia Ann Parker, a white woman who had been captured by the Comanches as a child and fully assimilated into their culture. Quanah’s mixed heritage made him a unique figure, bridging two worlds that were increasingly at odds.

After his mother was recaptured by Texas Rangers and returned to white society—a fate she reportedly resisted, Quanah grew up among the Comanches, rising to prominence as a warrior and leader during the turbulent years of the 1860s and 1870s. He led his people in resisting U.S. military campaigns, most notably during the Red River War. However, the relentless pressure of the U.S. government and the depletion of resources ultimately forced him to surrender in 1875.

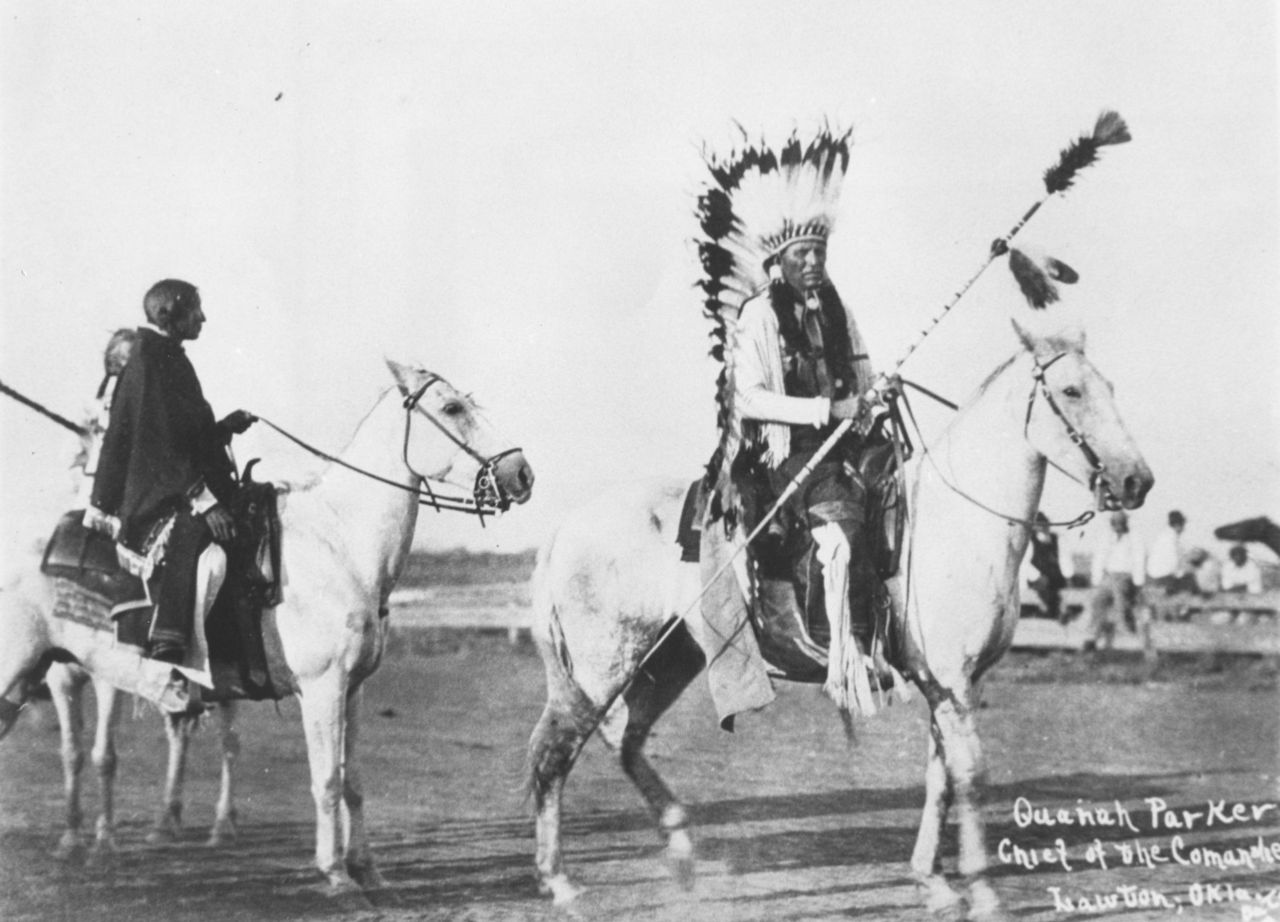

After his surrender, Quanah Parker took on a new role as a leader in the transition of the Comanche people from a nomadic, warrior society to life on the reservation. He settled with his people at the Fort Sill reservation in present-day Oklahoma, where he adapted to the changing world while striving to preserve aspects of Comanche culture.

Quanah became an influential figure, advocating for his people’s welfare and serving as a mediator between the Comanches and the U.S. government. He adopted many of the trappings of white society, including wearing Western-style clothing and building a large, Western-style home he called the “Star House.” At the same time, he remained a staunch advocate of Comanche traditions and spirituality.

One of Quanah’s most notable contributions was his role in promoting the Native American Church, which combined elements of Christianity with traditional Native beliefs and the ceremonial use of peyote. This movement provided a spiritual framework for many Native communities struggling to adapt to life on reservations.

Quanah also worked to secure better economic opportunities for his people. He negotiated grazing leases with cattle ranchers, ensuring that the Comanches received income from the use of their lands. His efforts earned him respect from both his own people and the wider American society.

Quanah Parker died in 1911, but his legacy endures as a symbol of resilience and adaptation. He is remembered as a bridge between two worlds, embodying the strength of the Comanche people while navigating the challenges of a rapidly changing world.

Today, the story of the Comanches serves as a poignant reminder of the costs of cultural destruction and the resilience of Indigenous peoples. While the Comanche empire no longer dominates the Great Plains, their history and traditions live on through their descendants, who continue to honor their heritage.

The rise and fall of the Comanches is a microcosm of the broader story of Native American tribes in the face of European colonization. It is a story of extraordinary achievement, profound loss, and the enduring spirit of a people who refuse to be forgotten.

Sources

- Gwynne, S. C. Empire of the Summer Moon: Quanah Parker and the Rise and Fall of the Comanches, the Most Powerful Indian Tribe in American History. Scribner, 2010.

- Hämäläinen, Pekka. The Comanche Empire. Yale University Press, 2008.

- Fehrenbach, T. R. Comanches: The Destruction of a People. Anchor, 1974.

- Utley, Robert M. The Last Days of the Comanche Nation. Yale University Press, 2004.

- John, Elizabeth A. H. Storms Brewed in Other Men’s Worlds: The Confrontation of Indians, Spanish, and French in the Southwest, 1540-1795. University of Oklahoma Press, 1975.

- Anderson, Gary Clayton. The Conquest of Texas: Ethnic Cleansing in the Promised Land, 1820-1875. University of Oklahoma Press, 2005.

- Native American Church history and cultural preservation sources from the Comanche Nation official website (www.comanchenation.com).