The Old West has no shortage of wild tales: gunfights at high noon, lawmen facing down outlaws, and dusty saloons buzzing with whiskey-fueled brawls. But among all the legends of frontier justice, few stories are as bizarre, or as tragically absurd, as the events of 1871 in Abilene, Kansas, when two men lost their lives in a heated dispute over a saloon advertisement featuring a comically well-endowed bull. This peculiar episode, which escalated from a simple painting into a full-blown shootout, even drew the attention of the infamous Wild Bill Hickok, one of the most celebrated lawmen of the Wild West. What follows is the strange but true tale of how a bull’s exaggerated anatomy became the catalyst for a deadly feud, a town’s moral outrage, and one of the oddest chapters in Wild Bill Hickok’s storied career.

Abilene, Kansas, in 1871 was a cattle town in every sense of the word. It was a bustling hub for cowboys driving herds along the Chisholm Trail, and its streets were lined with saloons, gambling dens, and brothels catering to the rowdy, hard-drinking men who passed through. Among the many establishments vying for attention was the Bull’s Head Saloon, a popular watering hole owned by two enterprising businessmen, Phil Coe and Ben Thompson.

Like any savvy proprietors, Coe and Thompson understood the importance of advertising. In an effort to make their saloon stand out from the competition, they commissioned a large, eye-catching mural to be painted on the side of their building. The artwork depicted a bull, a fitting symbol for a town built on cattle, emblazoned with the name of the saloon. But this was no ordinary bull. The animal’s anatomy was exaggerated to such an absurd degree that it left little to the imagination, and the result was both comical and provocative.

For Coe and Thompson, the mural was a clever bit of marketing designed to attract attention and draw in thirsty cowboys. But for the citizens of Abilene, many of whom prided themselves on upholding Victorian-era values despite the town’s rough-and-tumble reputation, the mural was an outrageous affront to decency.

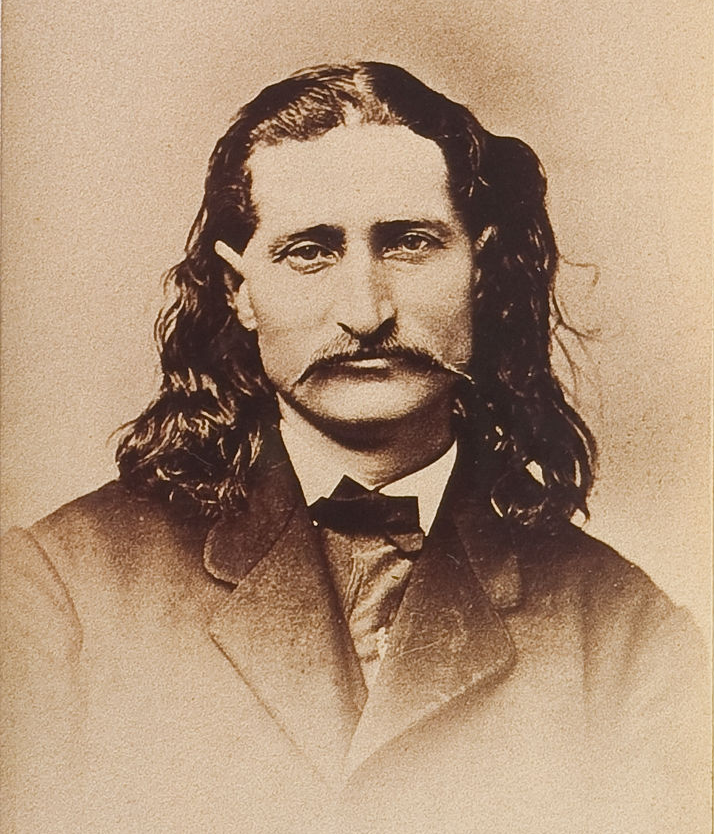

The reaction to the mural was swift and furious. Local townsfolk, particularly members of the burgeoning temperance movement and church groups, viewed the image as obscene and an insult to the moral fabric of their community. Gossip about the “vulgar bull” spread like wildfire, and the mural quickly became the talk of the town. Parents shielded their children’s eyes when passing by the saloon, while pastors railed against the depiction during Sunday sermons. The controversy escalated to the point where citizens began to pressure the town’s authorities to take action. The uproar eventually reached the desk of City Marshal James Butler Hickok, better known as Wild Bill Hickok. Hickok, a legendary gunfighter and lawman, had been hired to bring order to Abilene’s lawless streets. However, he probably never imagined that one of his duties would involve mediating a dispute over a cartoonishly endowed bull.

Wild Bill Hickok was no stranger to conflict. Known for his sharp shooting and larger-than-life persona, he had built a reputation as one of the most fearless lawmen of his time. But Hickok also had a pragmatic side. He understood the importance of maintaining peace in a town where tensions often ran high, and he recognized that the mural on the Bull’s Head Saloon was a powder keg waiting to explode. After hearing the complaints from outraged citizens, Hickok approached Coe and Thompson to discuss the matter. The two saloon owners, however, were unyielding. They argued that the mural was a harmless piece of humor and a clever advertisement, not the obscene spectacle their detractors claimed it to be. Coe, in particular, was known for his fiery temper and defiant attitude, and he refused to back down.

Despite Hickok’s efforts to mediate, the dispute reached an impasse. Frustrated by Coe and Thompson’s stubbornness, the townsfolk demanded that Hickok take more decisive action. Eventually, the marshal gave the saloon owners an ultimatum: either remove the mural voluntarily, or face the consequences.

What happened next is a testament to how quickly tempers could flare in the volatile environment of the Old West. Coe, feeling that his rights as a business owner were being trampled, became increasingly hostile toward Hickok. The two men exchanged heated words on multiple occasions, and their feud began to take on a personal dimension.

The tension finally boiled over on the night of October 5, 1871. According to accounts, Coe had been drinking heavily and was spoiling for a fight. When he encountered Hickok on the streets of Abilene, he reportedly brandished a pistol and fired a shot, though whether he intended to hit Hickok or simply provoke him is unclear. Hickok, ever the quick draw, returned fire, striking Coe in the stomach. The saloon owner succumbed to his injuries shortly thereafter.

Tragically, Coe was not the only casualty of the night. In the chaos of the gunfight, Hickok inadvertently shot and killed his deputy, Mike Williams, who had been rushing to his aid. The incident left Hickok deeply shaken, as Williams was both a close friend and a trusted colleague. It was a somber end to a dispute that had begun with a mere advertisement.

The deaths of Phil Coe and Mike Williams marked the end of the Bull’s Head mural controversy, but the incident left a lasting impact on Abilene and its residents. The mural was quietly painted over in the days following the shootout, and the saloon continued to operate under new management. However, the scandal remained a cautionary tale about the dangers of mixing humor, pride, and gunpowder in a town already teetering on the edge of chaos.

As for Wild Bill Hickok, the incident further cemented his reputation as a skilled but controversial lawman. While many praised him for his quick thinking and steadfast commitment to maintaining order, others criticized his handling of the situation, particularly the tragic death of Mike Williams. The incident weighed heavily on Hickok, and he left Abilene shortly thereafter, effectively ending his career as a lawman.

Looking back on the events of 1871, it’s hard to believe that something as seemingly trivial as a saloon advertisement could lead to such a catastrophic outcome. Yet the story of the Bull’s Head mural serves as a vivid reminder of the cultural and social tensions that defined life in the Old West. It was a time when personal pride often clashed with communal values, and when disputes were all too often resolved with gunfire.

The controversy also highlights the role of humor and art in challenging societal norms. While the mural was undoubtedly provocative, it also reflected the irreverent spirit of the frontier—a place where people pushed boundaries and defied conventions. In many ways, the painting of the bull was a microcosm of the broader cultural shifts taking place in America as it expanded westward.

Today, the tale of the Bull’s Head mural and the deadly feud it sparked has become a footnote in the larger-than-life legend of Wild Bill Hickok. It’s a story that combines the absurd and the tragic, the humorous and the heartbreaking, and it stands as one of the most unique episodes in the annals of the Wild West.

The Great Bull Controversy of 1871 is a story that could only have happened in the Old West, where larger-than-life personalities and a volatile mix of humor, pride, and moral outrage often led to unexpected, and sometimes tragic, consequences. While the mural on the Bull’s Head Saloon may have been painted over long ago, its legacy endures as a fascinating and cautionary tale of life on the frontier.

In the end, this bizarre episode reminds us that history is often stranger than fiction. After all, who could have imagined that a comically well-endowed bull would play a starring role in one of the most unusual, and deadly, chapters in Wild Bill Hickok’s storied career?